Original published in Canadian Woman Studies in the Fourth Fiction Issue, 2013.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

The Wallflowers

By

Joan M. Baril

The

band starts and the bride and groom swing on to the floor. Colleen is sitting

beside her Aunt Joyce at the family table, her hands on her lap clutching her

evening bag. She’d rather be anywhere else, anywhere in the world, but you

can’t skip out on your sister’s wedding.

Or can you?

At

the head table, the best man bows out the maid of honour. The ushers,

fulfilling their roles, partner the other bridesmaids. The six young women wear

sleeveless green silk with trailing white ribbons. A swirling forest waltzes to,

“You Light up My Life.” The blond bride, green piping on white satin, glows in

the centre.

Typical Dorion staging, thinks Colleen. Her

sister’s voluminous 1980’s gown matches her passion for retro music.

She

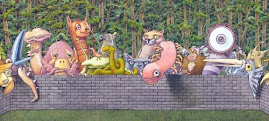

sees Sam Fellows, the groom’s cousin, walk over to the far wall where her

brother Guy is talking to three or four other men. They’re colonizing a wall,

she thinks, just like high school. A black and white male phalanx stands in

front of the bar, facing the dancers. She knows most of them, went to school

with many of them, is related to a few, but she knows none of them will ask her

to dance. They never do.

Her

mother and her new step-father stand up for “Chantilly Lace.”

“Your

flowers are wonderful, Colleen,” her mother says. “Unbelievable.” Her

step-father, Max, nods in agreement. They jive into the crowd.

Aunt

Joyce speaks in her ear. “The way you got itty-bitty rose buds twining around

the cake. Magic! What’s the variety?”

“A miniature,” Colleen tells her. “A

polyanthus rose called “The Fairy.” Very floriferous,”

“Just a minute. I’m going to write

that down.” Aunt Joyce scrambles in her evening bag for a miniature note book

and pen. But before she can open the tiny book, Mr. Fellows, the groom’s father,

approaches. He holds out his hand to Aunt Joyce who pulls herself up, flushing

with pleasure. Even when you’re seventy-five, it seems, you still love to

dance.

She’s

now alone at the table. The floor is crowded, mainly with married couples. A

waiter comes by with champagne and she takes a glass for something to do. As she

watches the dancers, tapping her toe to “Pretty Woman,” she keeps her eyes away

from the groom who seems to be dancing with each bridesmaid in turn. Alex

Fellows. Too good looking. Too nice. Ah, she thinks, lucky Dorion. Lucky

Dorion.

She

stands. The familiar feeling of failure engulfs her and she has to get out.

Like wallflowers everywhere, she’ll go to the restroom. Her Uncle Leon waves

her over, takes her hand and praises her table arrangements: posies of sweet

William and baby’s breath. If he were not crippled with arthritis, she thinks,

she’d ask him to dance.

In

the corridor, she stops. Other unattached women will have collected in the

restroom by now, putting on makeup, chatting and wasting time before going back

to dance with each other. As the evening progresses, they will start on the

shooters. Some will get drunk.

The

coat room is on Colleen’s right. Her shawl’s in there and also her cloth bag

with her secateurs, her packets of flower preservative and the low-heeled pumps

she wore when she came an hour early for a final flower tweak. She goes in,

slips the high-heeled torturers off and the pumps on. Flinging the shawl around

her shoulders, she heads for the front door but stops again. The smokers will

be clustered outside. She slips to the far end of the hall into the kitchen.

Here, before the reception started, she soaked the bouquets, snipped and

clipped, tweezed and wired. She crosses the shadowy space to take the emergency

exit.

Outside,

at the back of the building, a single bulb lights the parking lot and the

dumpster by the brick wall. The music thumps through. “Mama Mia.” She weaves

among the cars to the sidewalk. She’s now an escapee. But not for long. If she

stays away more than thirty minutes, her family will notice, start asking

everyone, whispering with each other. “Have you seen Colleen?” She cringes to think of it.

The

last of a July sun splotches the asphalt, its warmth lifting out the pavement

smells, the garden smells from behind hedges and fences, the food smells from

narrow houses just putting on their evening lights. A faint breeze waltzes by

moving her silk skirt around her ankles. In the vanishing light, her dress

glows a peachy apricot, her favourite colour, the shade of certain martagon

lilies. She slip-steps, swinging her body, making the silk glimmer. Each front

yard holds a puddle of shadow and some sort of flowers. Happily alone now,

light footed, she dances along the sidewalk, mouthing, “Ob La Di, Ob La Da,

Life Goes On,” glimpsing shasta daisies, a row of cosmos, bleeding heart, a

dark line of monk’s hood.

It’s

ridiculous to be so sensitive at thirty years of age. It’s ridiculous to be

ashamed of being a wall flower. To be defined by male approval. She’d always

been a wall flower, even in high school. Why can’t she just sit, tap the toe,

enjoy the music? Why not dance with her girl friends; why wait for a male?

She

turns at Gratton Street, slows to walk up the hill. The street where she was

born. The old narrow insul-brick house hides behind a long glass veranda.

According to her mother, in 1978, a gang of hippies lived next door, coming and

going at all hours and playing the Moody Blues half the night. They must have

been the last hippies in Thunder Bay, she thinks. What would it be like to live

with a large group of friends, people filling the house with talk, the music

always on? No shortage of dance partners there. Shared dinners, she thinks, and

lots of laughter. She stares at the former hippie house, a brick three storey,

now dark with blinds drawn. The truth stares back. If she’d lived there, she’d

have been miserable.

Genes,

DNA, one’s early life, whatever. One’s fate. It designs your inner being, sends

you out and you follow its path, no matter how the world temps you otherwise.

Colleen’s

father died when her sister Dorion was four, her brother Guy a baby. She was

six, old enough to have vague memories of his tobacco smell, his prickly

unshaven face. When he came home from a trip north, he let her rub his whiskers

before he shaved them off. But she has no memory of the day his prospecting

buddy arrived on the porch and her mother fell screaming at the man’s feet. Yet

she was present, she’d been told later by Aunt Joyce. Luckily, her guardian angel

also incised the funeral from her brain, leaving behind some blurry shadows, a

few faces and voices, the smell of the carnations, the texture of their leaves.

Now,

when her relatives mention her father, they always say the same thing: he missed the big news. But she remembers it very well.

January 9, 1995, a sloppy day of winter thaw. She was seventeen and in Grade

Thirteen. After school, she sprinted home because a split along the sole of her

Wal-mart boots was sucking in water and she wanted to get home before her toes

froze. She’d not told her mother about the leaking boot. She dreaded the look

on her mother’s face, the brief sweep of despair before the smiling gloss took

over. “Don’t worry, Darling One, we’ll manage somehow.” The lilt in the words

always made her wince inwardly.

She

rushed up to the bedroom to change her soaking socks. Dorion sat at the tiny

dressing table painting her nails black to match her heavy black eye liner, her

black spiked hair, her black clothes and black lipstick all contrasting with

the multiple studs winking in her nose, ears, and eyebrows.

A shout from downstairs. “Colleen!”

Her mother home so early? “Dorion, come down now! Guy where are you?” She heard

the basement door open as her mother shouted down the backstairs to her

brother’s bedroom.

They gathered at the kitchen counter

in shock. Steaks? Their mother had brought home two large T-bones for dinner

and was now cutting them to fit the two battered fry pans. The steaks were

marbled with veins of pale yellow fat and had a distinctive smell, sweeter than

hamburger or stew meat.

“Where did you get them?” Colleen

whispered.

“Maltese’s Meats,” her mother said

gaily. “Steak is nothing. Get ready for the news, kiddos. The family train has

jumped its rusty track and we’re sailing the super highway.” She circled the

knife above her head, doing a little jig. In the other hand, she held an

inch-thick slab which she dropped into the smoking grease. “I’m quitting my job

at the radio station at the end of the month.”

Colleen

tried to speak, but couldn’t. Her mother had worked in the office of CXYY as

long as she could remember. A big squeeze of worry pressed her stomach.

“I’ve

signed up for an evening real estate course.” Her mother was pulling out

several containers of salad from a grocery bag, ignoring the looks exchanged

among her children. “You kids probably don’t remember but Dad left me his

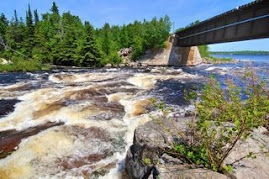

mining claim in Gracie Township. You can’t get there, except by float plane.

But today, I learned the province is building a road to a palladium mine the

next township north. I saw the map. Hot news at the station. The road will

swing right by our lakes and I’m going to divide the land into cottage lots and

sell them all—rocks, trees, beach, swamp, the bleeding lot.” She set a slab of

brownies and a cheese cake in the middle of the table. “The market’s on fire.

Everyone wants a summer cottage and now they’ll get one. A dream cottage less

than ten miles from the city.”

“You’re going to sell my lake?”

Colleen’s sister wailed. Dorion Lake was

the largest of the four with islands and long beaches. Her lake, Colleen Lake,

sported a marsh at one end, or so she’d been told by Uncle Leon. She was sure

the swamp would be rife with wild orchids. She’d dreamed of flying in one day

after she started working and made some money. She’d camp there, canoe the lake

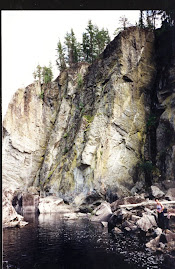

and catalogue the plants. Guy Lake was rocky with a spectacular cliff gracing

the far end. The lakes created a rough necklace of three, with her mother’s

lake, Kate Lake, behind the others. “The most beautiful,” her late father supposedly

had said, “and so I named it after my wife.”

“It’s not your lake, Dorion, dear,” her mother

said to her younger daughter. “The lakes are mine. But, I’m going to set up

trusts for you kids, splitting the money into four parts. After supper, I want

each of you to write me a list of the five things you need right away. I went

to the Royal Bank this afternoon and asked for a ten-thousand dollar loan.”

Colleen gasped at the others who both gasp back at her like beached whales.

“With those lakes as collateral,” her mother went on, “it’s a snap to be

approved. I’ll probably get the money tomorrow.” She threw some cutlery in a

heap in the centre of the table. “Nosh on, you lucky rich kids,” she said.

Colleen ate the steak and wrote her

list at the same time. She could not touch the salad or dessert. She didn’t

want to think about the bank loan or her mom leaving her job. She wrote:

1.

Don’t sell the marsh on my lake. There might be orchids.

2.

Snow boots

3.

A winter jacket

4.

A subscription to “Fine Gardening.”

5.

A dress for the Valentine’s dance.

She

had made herself believe if she had the right clothes, then, for once, she’d

enjoy the dance. Somone, perhaps a boy from her class would ask her to

dance. A hard but necessary lesson. The

dress did not deliver.

Dorion

tore up several lists. A week later she handed hers in.

1. An

Aljean kilt in Hunting Fraser tartan and short black velvet jacket.

2. Abercrombie

and Fitch clothes

3. A

cashmere pant suit – Ralph Lauren with Coach bag and shoes to match.

4. Hairdresser’s

for a cut and colour – white blond

5. Tommy

Hilfinger casuals with leather boots.

At

fifteen years of age, Dorion morphed overnight from a Goth to a Preppie.

Twelve-year-old

Guy had trouble with his list. It contained two items.

1. Downhill

skis.

2. Save

so I can go to medical school.

Now,

Doctor Guy Gathercole is off to Kosovo with the Red Cross at the end of the

month. Before her wedding, Dorion moved her boutique to the Internet. And

Colleen has a garden, a ten-acre paradise on land she bought from Uncle Leon.

She designed a small house jewelled with windows. She makes her living as a

hybrid: one who can photograph, paint, sketch and write about flowers. Slowly,

she too is morphing. She’s becoming an expert, seen in magazines and on TV.

She’s in demand.

But

not at a dance.

Once,

a year ago, when Dorion dropped by to get flowers for her shop, she’d asked

why. Her sister grimaced in embarrassment. “Guys are like weeds; they’re

everywhere,” she said. “You’re not half bad looking, Colleen. Someone will

drift by one of these days. But your problem is you’re too insular. You like

things the way they are.”

Colleen

almost said, “I don’t want to be insular. I want to be loved. I want to love. I

want to get married and have children, like normal people. Like you.” But she

felt her throat seize up. Each sentence seemed shadowed as if a parade of

perverse imps lurked behind them, refuting them. She’d bent to clip fulva

lilies and false spirea, filling two silver bowls, her hands shaking in

confusion.

Now, she walks back down the Gratton

Street hill to still more music from Mama Mia. “Waterloo.” She can hear people

singing along. She had a few boyfriends in university. She lived with Bruce

Bonnycastle her entire final year. He was a great dancer but he was too big for

the little apartment. He was always there: talking to her, including her,

making plans, asking her opinion, trying to make her come up for air, to be

present. She could not think, she could not read, she could not sketch or dream

or design in her head. Her brain closed down. For two weeks that spring, she

twisted in shame until she understood the extent of the waste, the travesty of

the relationship. She was living with him because that’s what women did. Women

had boyfriends. They moved in with the guy. They were together forever. The

thought gave her the horrors and so did the shame at her dishonesty to herself

but especially her dishonesty to him.

She

broke the news to him after the graduation dance.

Back inside, she slips on her heels,

repairs her hair and lipstick. The dance floor is crowded. The single women are

jiving up a storm. “Take a Chance on Me,” bellow the guests. The same men stand

and watch. Why don’t they dance with each other, she thinks, get out on the floor

and have some fun? It’s ludicrous, pitiful, laughable. Just as idiotic as she

is. She walks over to her brother Guy on his wall.

“I’d like to dance with you before

you go away,” she says ignoring his surprise. “Will you do me the favour?” They

float out to “Unchained Melody.” Guy dances like he skies or plays hockey, with

such grace he makes it look easy. Her apricot silk flares around her legs. Her

feet in the expensive heels move like delicate leaves caught by the wind. The

single women don’t dance to the slow music. Chatting and laughing, they head

for the tables or the bar. The bride and groom are nowhere around. She hopes

she’s missed the bouquet toss.

“I caught the garter,” Guy says in

her ear. “I’m taking it to Kosovo.”

“I’ll miss you,” she says. “I hope

the garter brings you a wonderful wife.” He laughs. The band segues, speeds

into “Dancing Queen.” Her mother waves during a complicated step. Colleen

decides that later she’ll ask her new step-father for a dance.

“Do you want a drink?” Guy says.

“No, I’m going to dance with Posie

and the other gals. Then I’ll come over and join you at your wall.”

Later,

at home in bed, watching the moon top up the garden, she remembers she almost

said, with the other wallflowers.

She’s glad she didn’t say it. Her body still feels energized but her mind is

melting into sleep, forsaking her thoughts about men, about women, about

herself.

She

thinks about her brother off to Kosovo, the bride’s garter tucked into his bag.

And she has a new brother-in-law, the handsome Alex. But he’s more than a

single person, she realizes. Alex’s entire family is now linked to hers,

tendrils emerging and merging, just as, a few years ago, the numerous kin of

her new step-father were slowly grafted on.

Sprawling

vines of connections.

She

turns over into a happy thought. Her

Aunt Joyce is coming to tea tomorrow. She’ll pick a special bouquet for the tea

table.

The

dark yellow lilies called Fata Morgana

are just moving into bloom.

Original published in Canadian Woman Studies in the Fourth Fiction Issue, 2013.

Original published in Canadian Woman Studies in the Fourth Fiction Issue, 2013.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment