Tuesday, October 10, 2017

Margie Taylor Reviews Nobel Winner Kazuo ishiguro's A Pale View of Hills.

So says the narrator of Kazuo Ishiguro’s debut novel, A Pale View of Hills. Published in 1982, the novel was praised for its “uncanny mix of surface calm with menace and deep tension”, a mix that would be repeated seven years later in his best known work, The Remains of the Day.

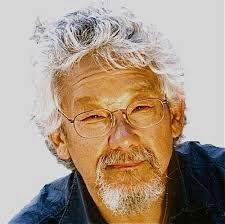

In announcing that Ishiguro had won the Nobel Prize in Literature 2017, the secretary of the Swedish Academy described him as a writer “who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” It is that false sense of connection that confronts not only the characters in his novels but the reader as well, when we realize that the story as written is not necessarily in alignment with the facts.

A Pale View of Hills is set in England and in postwar Japan at the time of the rebuilding of Nagasaki. Etsuko is a middle-aged Japanese woman now living alone in the English countryside. Six years ago her oldest daughter, Keiko, hanged herself. During a visit from her younger daughter, Etsuko begins dreaming about a young girl, Mariko, the child of a woman she knew one summer in Japan.

The way it’s told, Etsuko is pregnant that summer and the woman, Sachiko, intrigues her, partly because she’s further down the road of motherhood. But Sachiko is an indifferent mother at best. Although given to lecturing Etsuko on the things she’ll find out when she, too, is a mother, she raises Mariko with a carelessness that verges on abuse. Even when it becomes apparent there’s a child murderer in the area, Sachiko remains indifferent, letting her daughter wander at will.

Mariko is not a happy child. She and her mother have a troubled relationship, and she professes to hate her mother’s boyfriend. In spite of announcing several times that her daughter’s welfare is of utmost importance, Sachiko continues to make plans for her own happiness, at the expense of that of her child.

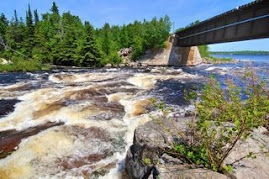

Etsuko, who is pregnant, has her own unhappiness to contend with. She spends her days alone in her apartment, from where she can look out past the trees on the opposite side of the river. Beyond the trees she can see “a pale outline of hills visible against the clouds. It was not an unpleasant view and on occasions it brought me a rare sense of relief from the emptiness of those long afternoons I spent in that apartment.”

There are numerous similarities between Etsuko and her friend. Sachiko schemes to marry an American and leave Japan; Etsuko will eventually marry a foreigner and move to England. Like Sachiko, she will have a difficult relationship with the child she is carrying – so much so that she will bear some guilt for her daughter’s eventual suicide.

At the risk of giving away the plot, for those who haven’t read it, the twist comes near the end of the book. Etsuko, who has gone looking for Mariko, finds the child crouching on the bank of the river. The girl says once more that she doesn’t want to go away – she doesn’t like her mother’s boyfriend, she thinks he’s a pig. Etsuko replies angrily that she’s not to talk like this, adding, “In any case, if you don’t like it there, we can always come back.”

It’s this sudden change in voice – the use of the word “we” – that startles the reader. Are Etsuko and Sachiko one and the same person? Is Mariko actually Keiko, the daughter who hanged herself? A paragraph a few lines on leads us to wonder: did Etsuko kill the child that night on the river-bank? Is it possible her daughter’s death was not a suicide at all?

Ishiguro has said he was trying something a little “odd” when he wrote this book. He wanted to show how people use language to deceive and protect themselves. “So the whole narrative strategy of the book,” he said, “was about how someone ends up talking about things they cannot face directly through other people’s stories.”

What can be said for sure is that nothing can be said for sure about this story. The author is intentionally ambivalent; the ending is purposefully ambiguous. And the narrator, Etsuko, is unreliable. Is the story she relates really that of her friend, Sachiko? Or is she remembering a painful event in her own life – one connected with leaving Japan and the subsequent death of her daughter?

Kazuo Ishiguro has been compared to Jane Austen both for his “carefully restrained mode of expression” and for the important things he leaves unsaid. Because we so frequently equate that restraint with something inherently English, it came as a bit of a shock for many readers to learn that the author of Remains of the Day was born in Japan, moving to England when he was five.

But Ishiguro, of course, is a hybrid – which so many of the very best English writers are and have always been. Joseph Conrad was born in Ukraine – Henry James was from New York – Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth were born in India. In my own mind what foreign-born writers bring to the scene is a certain detachment – an ability to stand apart from one’s fellow citizens and regard them with a more objective, even jaundiced eye. Ishiguro alluded to this several years ago in an interview with The Telegraph:

“There is that slightly chilly aspect to writing fiction,” he said. “You do have to be slightly detached to say: how would human beings respond in this situation?”

I love that word – “chilly”. Not cold, but cool … deceptively muted. Take, for instance, Etsuko’s description of how she is haunted by her daughter’s suicide and the fact that it was several days before her body was discovered hanging in her room:

“The horror of that image has never diminished, but it has long ceased to be a morbid matter; as with a wound on one’s own body, it is possible to develop an intimacy with the most disturbing of things.”

That, I would say, pretty neatly sums up Ishiguro’s oeuvre to this point: intimate, restrained, and disturbing.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment