Tuesday, February 20, 2018

An oldie but a goodie. Margie Taylor, our extraordinary reviewer, tackles The Thirty Nine Steps.

As a teen ager, I loved this book. I think I read it a couple of times. At the time I was hooked on adventure stories so of course I read other Buchan books but this is the only one I remember. As usual Margie Taylor gives an insightful review of a classic.

“I returned from the City about three o’clock on that May afternoon pretty well disgusted with life.”

This, I think, is a perfect first line. Why is he – if it is a he – disgusted with life? What’s happened up to now? And what is about to happen on that May afternoon that will change things? We’re immediately drawn in, and, in the case of The 39 Steps, we’re not disappointed.

Published in 1915, John Buchan’s thriller takes place during the spring and early summer of the previous year. A European war is pending, and Richard Hannay, a 37-year-old former mining engineer, has returned to England from Rhodesia, having made a comfortable pile of money. He’s been back in the “old country” for three months and is fed up with it:

“The weather made me liverish, the talk of the ordinary Englishman made me sick, I couldn’t get enough exercise, and the amusements of London seemed as flat as soda-water that has been standing in the sun. ‘Richard Hannay,’ I kept telling myself, ‘you have got into the wrong ditch, my friend, and you had better climb out.'”

He’ll give it one more day, he decides; then, if nothing changes, he’ll head back to Cape Town. That night, as he’s unlocking the door to his apartment, he’s accosted by a stranger, a nervous little man who asks to speak to him for a minute. Hannay invites him in – trusting soul, isn’t he? But it was different times. Anyway, if he’d brushed him off, we’d have no story.

After ensuring that the apartment is locked, the stranger, an American named Franklin P. Scudder, lays out the details of a nefarious plot – I use the word advisedly – involving German anarchists, British military secrets, and the assassination of the Greek prime minister during his upcoming visit to London. Scudder, a kind of freelance spy, must lie low until the day of the visit, at which point he’ll alert the authorities and thwart the anarchists. It’s no use alerting them sooner – the prime minister’s visit would be canceled and the Germans would merely find another time and place to do him in. Everything must go ahead as planned until the very last minute.

Unfortunately, Scudder’s whereabouts have been discovered and his life is in danger. To throw the killers off the scent, he has faked his own death and is hoping Hannay will agree to let him hide out with him for the next few weeks. Deciding he likes Scudder and, more important, trusts him, Hannay agrees. Scudder provides a few more details over the next few days, expressing the hope that if something happens to him, his new friend will do his best to take his place. He mentions several things, in particular a Black Stone and man who speaks with a lisp. And someone else, who Scudder can’t speak of without shuddering: an old man with a young voice who can hood his eyes like a hawk.

During this time, Scudder continues to fear for his life, and rightly so. One night Hannay returns home to find Scudder lying dead, a long knife skewering him to the floor. He’s been killed because of what he knows, and Hannay figures he’s next. He can’t call the police, as he’s now a prime suspect in Scudder’s murder. His only option, he feels, is to go into hiding until he can stop the spy ring and clear his name. He boards an express train to Scotland, taking with him Scudder’s notebook, which contains the details of the plot written in code.

The 39 Steps is one of the earliest examples of the “innocent-man-on-the-run”, a format that’s been used many times over the years – The Fugitive, North by Northwest and The Bourne Identity come to mind. Like much of the genre, the story contains a number of fortuitous, but unlikely, coincidences. Right at the moment when our hero is about to be nabbed by either the police or the Germans, an offensive little fop named Marmaduke Jopley, whom Hannay met in London, just happens to come by in a touring-car, offering Hannay a chance to disguise himself and escape through the police cordon. Keep in mind that we’re now in the Scottish highlands, more than 500 km from London and at least a two-day drive back then. And yet, here he is. How, as I said, fortuitous.

Buchan, like many English writers before him, was fond of aping the dialect of “country folk”, often with unfortunate results. Here, for instance, we have a speech by a Scottish roadman – who is, of course, drunk. (My apologies to my friends of Scottish heritage):

“The trouble is that I’m no sober. Last nicht my dochter, Merran, was waddit, and they danced till fower in the byre. Me and some ither chiels sat down to the drinkin’ – and here I am. Peety that I ever lookit on the wine when it was red!”

Yikes.

Still, Richard Hannay is an appealing character – a civilian everyman given the chance to be brave and selfless. You find yourself cheering for him all the way through. When Alfred Hitchcock filmed the book in 1935, he spiced it up by providing Hannay with an attractive blonde companion and replaced Scudder with a female spy named Annabella Smith. Neither of these women appear in the book; the story works quite well without them. Also, in the film, the “39 steps” refers to the German spies – in the book, it doesn’t.

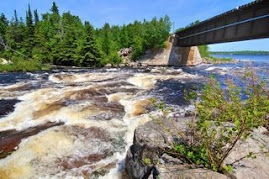

John Buchan was Canada’s Governor-General from 1935 until his death from a stroke-related head injury in 1940. He was a prolific author, having produced almost 30 novels, seven collections of short stories, and a handful of biographies. But it’s his tale of espionage, followed by four more Richard Hannay thrillers, for which he’s best remembered, and deservedly so.

As writers and readers we should also be grateful for the author’s legacy of his time in office: the Governor-General’s Literary awards. Thank you, Mr. Buchan.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment